To Be a Good Writer Is to Be a Great Witness

Canal Street News Summer Journalism Club member Irene Hao reflects on finding her voice, lessons learned in quarantine and the art of James Baldwin.

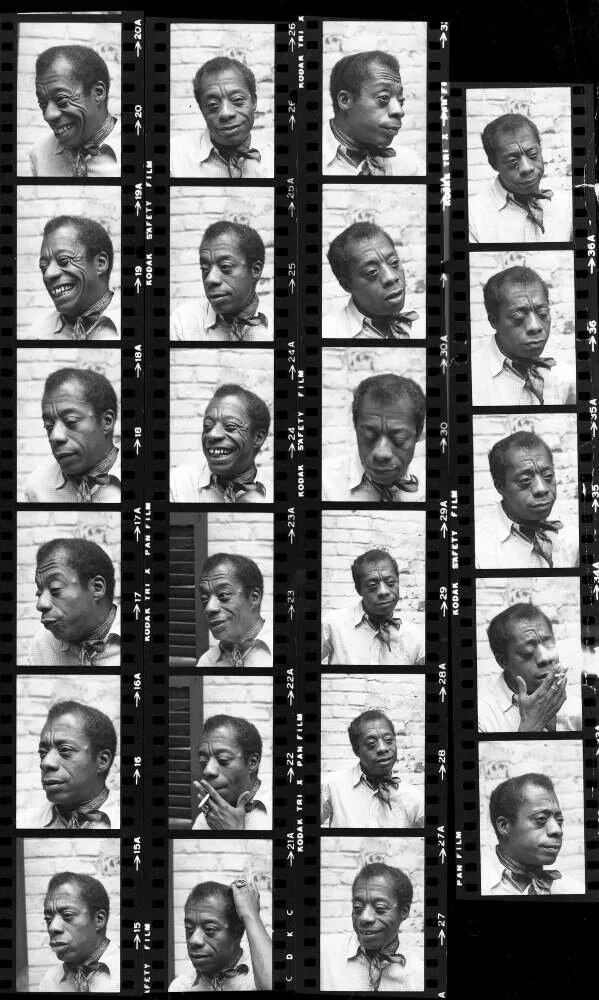

Photos of Baldwin outside of his Manhattan apartment in 1972 by George Goodman for the New York Times

“Part of my responsibility—as a witness—was to move as largely and as freely as possible, to write the story, to get it out.” —James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro

Trapped in an air-conditioned room all spring, I sit in my quiet bedroom. Months ago, I would’ve given anything to spend the rest of my junior year at home; to not operate on four hours of sleep and two cups of coffee every morning; to have the time to do online classes and hobbies and time for myself. But an invisible killer arrived in New York City, and now I am stuck in this bedroom, safe from the killer but unable to help.

It’s a surreal experience. There’s no bell to dictate which floor or room I have to be in at certain times of the day, no classmates to gossip on the latest Harry Styles album or complain about yet another U.S. History essay to listlessly type, no sunset to admire as I make my way to the subway ride home. Instead of blue summer skies, I gaze at the blank white walls and ceilings of the apartment I share with my parents and younger sister. There’s no hospital nearby, no frequent ambulance sirens, no 7 p.m. applause for the emergency workers in my neighborhood—just silence. I gaze at the empty sidewalks, the accumulating piles of garbage bags, the rats scuttling about and the eerily silent park across the street. I gaze at my neighborhood through my bedroom window.

I’ve retreated to my shell in quarantine. My apartment is a glass globe. I’m hit with this feeling that what is happening right now is unprecedented and that I will go down as part of history, but I know that my name will not appear in the textbook a century later. I won’t be immortalized as a statue in Central Park, rather, right now I exist as a mannequin displayed in a store window. I gaze beyond the glass at the people passing by, but make no attempt to join them.

I am a witness.

The blank white walls of my bedroom are akin to a mental asylum, a prison. I’ve been trapped in 1,000 square feet of mental degradation and boredom. I turn to the internet, but current events don’t do much to lighten the atmosphere.

Like James Baldwin, I have been a witness to many things. I have lived through the election of Barack Obama and Donald Trump, the economic crash of 2008, Sandy Hook, Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Sandy, the remembrance of 9/11 through a memorial and museum, the fads championed by Souja Boy and Gangnam Style, and the ascension of artists like Justin Bieber and Rihanna. Now, I live in the time of the peak K-pop fandom, the coronavirus pandemic, Black Lives Matter protests.

I have been a witness to loss, love, joy, rage, frustration, ignorant bliss and the bitter truth. I have been so much of a witness that I fear the day when I look away. In the spirit of Baldwin, I am not a member of any major organization representative of my beliefs or race or gender. I am a woman, yet I am not a member of the Stuy Feminist Club. I am Asian, yet I am not a member of the New York City Asian American Student Council (NYCAASC). I identify as bisexual, yet I have neither gone to a Pride parade, nor am a member of Stuy Spectrum. I am a witness, a scared witness, so scared that if I were to identify with a certain group in society, I feel I would lose all opportunity to form connections with someone not in that society, for I strive to be a decent human being, a friend to anybody and everybody, even my racist or homophobic peers.

As a witness, I’ve watched people imitate zebras banding together on the African savannah, their black and whites stripes confusing the lion—we all tend to flock together with those who look like us. In an attempt to protect ourselves, we crowd together like sheep on a green meadow. But like the black and white lines of the zebra which confuse the lion’s eyes, I have long witnessed—in both the record books of history and in the present recording of today’s events—the mind-boggling black and white lines of society, and my eyes are strained and tired.

Thus, I try to look away. Yet, I can’t help but gaze with rose-colored glasses at the political arguments between my parents, the discussions in my English classes, school newspaper articles, and I am compelled to ask myself who I truly am and what my role and future in this country are like.

“Who am I?” I first asked myself that question as I sat down to write a seventh-grade essay assignment. I wrote about my love for art, for writing and for people. I wrote but with the constant impression that I would be reading this essay out loud to my classmates and therefore, must be in some degree impressive and inspiring. My seventh-grade self sought to showcase the best of me and believed that if I did, more of my classmates would be willing to approach me and become my friend.

I am a writer. I strive to use my writing for the benefit of society, whether that be in a poetry slam, in songwriting for school productions, in newspaper journalism or in the hidden contents of my memo app and dream journal.

I am a writer, who has struggled to find her voice. It began in the classroom. I was the typical shy, quiet Asian nerd who excelled in all subjects, except music. I refused to learn music theory or the piano; thus, I was stuck with drums for a summer or two. I never raised my hand unless I was called upon. I dreaded presenting projects. I was often asked to speak up. I didn’t look my teachers in the eye when I talked to them, which I now regret as it was likely disrespectful. I achieved high marks in all areas, except class participation, which was a typical situation in the Brooklyn neighborhood I grew up in. Then it was with my family. Until recently, my parents aren’t the most publicly or openly affectionate—an atmosphere of scolding, constant nitpicking and sighs of frustration paint a better picture of my reality. I used to dread when my father would come home from work. I was the same quiet kid at school as I was at home. But writing helped make me who I am as a person. Through venting my pent up emotions on paper, I gained the courage to put those same emotions into spoken words.

I am Irene Hao, a writer. It is how I have long identified myself, though I hardly am as familiar and fluent and eloquent with the English language and with public speaking as Baldwin and countless civil rights activists and opinionated figures before me.

I am a female bisexual Asian American with a knack for spinning ideas into words— then spinning those words into poetic forms. My role in this country of diverse people and voices is to add my voice to the melting pot and to be unafraid to do so.

I see my future in writing not just as a witness, but about this country—and about me.